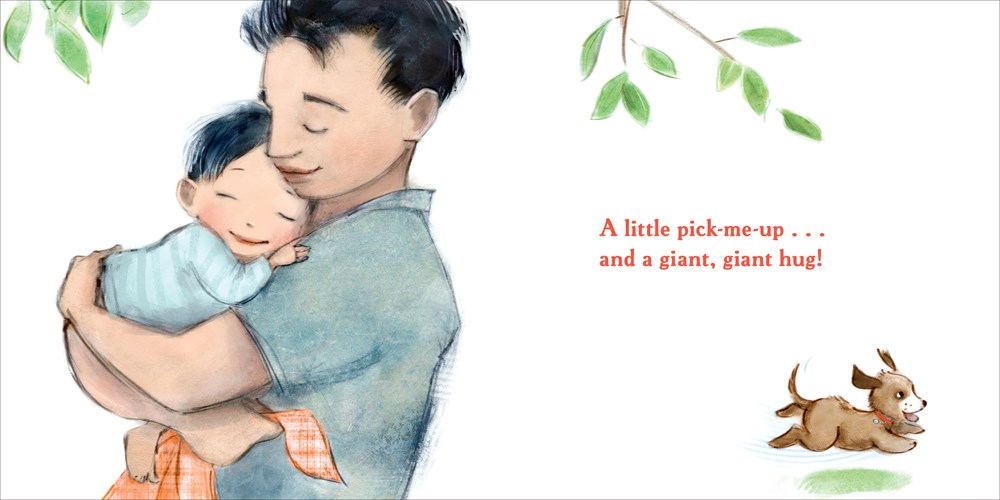

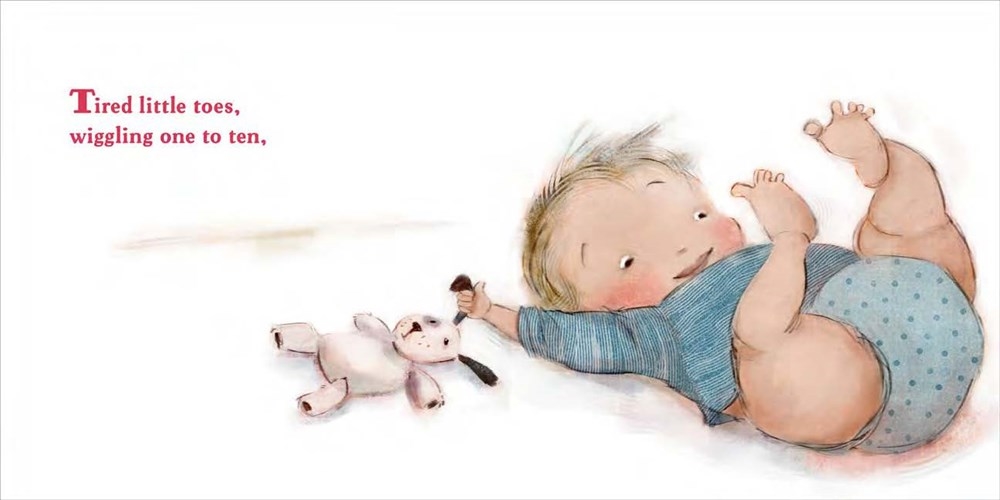

Little Bitty Friends

by Elizabeth McPike; Illustrated by Patrice Barton

Putnam Books for Young Readers (February 2, 2016)

Welcome Elizabeth McPike to Kid Lit Frenzy. Thank you for stopping by and answering a few questions.

What prompted you to start with books for very young children (toddlers)?

Well, I know I don't have to convince your audience of the importance of reading to children from the earliest age, but I do want to mention a couple benefits that rank high on my list. I recall a story I have always liked. A mother arrives home to find her college-student sitter -- with the baby in her arms -- reading aloud from a novel that she had been assigned in one of her college classes. The mother's first reaction was to find this somewhat ridiculous -- Faulkner or Joyce for a two-month-old? But then, as she thought about it more, she realized that reading almost anything in the language the baby was just beginning to hear and learn would immerse her in its essential sounds and rhythms.

Now I am most definitely not writing (or recommending) adult novels for tots when there are so many good books targeted to this age group, but this story makes a good point. The ability to distinguish sounds one from another, to mimic them, to pull them apart and put them back together is the earliest and one of the most critical pre-reading skills. Only much later, of course, will a child learn to map these sounds onto letters or combinations of letters. So, yes, for a host of reasons, I am passionate about early -- very early -- reading, and am happy to be writing for this important age group. And I am thrilled that my first book, Little Sleepyhead, has just been chosen by the Dolly Parton Foundation as part of its program to put free books into the hands of hundreds of thousands of children who otherwise would not have a home library.

Another reason I am so interested in this age group stems from the crucial relationship between knowledge and reading comprehension. No matter how fluent a reader a child eventually becomes, if he does not have the requisite background knowledge, he will not grasp the meaning of a given passage, and meaning after all is the end goal of reading. Numerous studies have shown that vocabulary -- especially nouns -- is a convenient proxy for more general knowledge. If you know what a meadow is, for example, chances are you have some surrounding knowledge -- maybe small, maybe significant, but something -- that relates to that word. So, word knowledge and the broader background knowledge it portends is key to comprehension. And -- to my point here -- there is a vast difference in the vocabulary found in written vs. oral speech.

In one of the most important studies every conducted in the fields of education, early learning, and social policy, the lexical range and complexity of written language was compared to that of spoken language. Written texts of all sorts and levels were examined against key language gauges -- vocabulary, complexity of construction, etc. These written texts included everything from pre-school children's books to newspapers and magazines to scientific abstracts. The analysis of spoken language was equally varied and comprehensive: TV shows of all kinds, mother's speech to their children at various ages, conversations between college-educated adults, and even expert witness testimony for legal cases. The findings were both potent and staggering. Here, in two sentences, is how a leading researcher in the field summarized the results:

"Regardless of the source or situation and without exception, the richness and complexity

of the words used in the oral language samples paled in comparison with the written texts.

Indeed, of all the oral language samples evaluated, the only one that exceeded even pre-school

books in lexical range was expert witness testimony."

Let that sink in: The written text in a book for a pre-schooler is richer and more complex, with more varied vocabulary and linguistic construction, than a conversation between college-educated adults!

So, there you have it. Books, books, books. Reading, reading, reading. And early, early, early, because knowledge is accumulated gradually. We should all be reading to our children. We should be reading to other people's children. We should harken to the special meaning these findings have for a democratic society, for basic fairness, for the roots of inequality, and for the poor among us. The knowledge gap between those who are read to early and those who are not is expressed not in a linear equation but an exponential one. Over time, we are not looking at parallel lines. Rather, we are looking at a gap that grows bigger every day, until it is a chasm. If this doesn't make one passionate about good books for this young age group, nothing will.

I also enjoy writing for the zero-to-three crowd because I am a long-time lover of poetry. (Beware: I often press upon the unsuspecting a little paperback gift entitled, By Heart: 101 Poems To Remember, edited by Ted Hughes.) When I write for this age, I get to indulge myself. Of course, I'm not writing poetry per se, but I do make heavy use of rhyme and rhythm, repetition and alliteration. So this is a double-scoop cone: I enjoy playing with poetic elements, and young children thrive on hearing them. And of course presenting sounds, language, and ideas in this form is yet another way to help children develop essential pre-reading skills, If I write, for example,

the noisy blue jay,

jabbering all day,

where does he go at night?

Not only is the young child introduced to an outstanding verb -- and one that a parent reader can play with to elicit a giggle..."jabber, jabber, jabber" -- but in addition the child hears the long /a/ sound and the consonant /j/ sound twice, both embedded in rhyme and alliteration. Because of the context, the repetition, and the rhyme, he is more likely to enjoy and remember the sounds. And because the syllables are set to a beat, tuned like music to delight the human ear, they help foster both listening skills and an early love of language. It's no mystery why nursery rhymes have persisted for hundreds of years. "Ride a cock horse / to Banbury Cross..." is still hard to top for its ability to get inside your head.

What are your favorite bookstore hangouts in DC?

I was delighted to have recently read that young adults are re-discovering the virtues of brick-and-mortar bookstores! And I am equally delighted that you asked this question, because it gives me the opportunity to sing the praises of and express my gratitude for one of the truly outstanding bookstores in the country. I have the good fortune to live two and a half blocks from Politics & Prose bookstore. You may have heard of it; about a dozen years ago it won the award for the best independent bookstore in the country. It has free author talks every single day of the year except for a few major holidays, and I am hard put to name a prominent author who has not appeared there. It also offers both literature and writing classes. This Winter's classes -- to name three -- include ones on memoir writing, on Ralph Ellison's short fiction, and on the "Golden Age of Ladies' Detective Fiction," which covers British authors such as Dorothy Sayers, Josephine Tey, and Agatha Christie. There's a large children's department, a coffee shop, and comfortable wing chairs scattered about. It is a true neighborhood (indeed, city-wide) treasure, a fact not lost upon real estate agents, who are quick to include "close to P&P Bookstore" in their listing ads.

And did I mention that it has the best remainder section of any bookstore I've been to, and I've been to a lot. When my kids say to me, referring to some obscure topic, "Mom, how do you know about that?" -- I was recently regaling them, for example, with harrowing tales of Teddy Roosevelt's journey down an unexplored tributary of the Amazon -- I explain that my reading is in large part governed not by any particular scheme or by a bucket list of books I should read but by what's on offer in the Politics & Prose remainder section! The store has been a great blessing in my life. I am there three or four times a week. Feeling down or bored or in need of company, or want to browse through a just-released book before deciding whether to buy: out the door I go to P&P!!!

Are there other book projects in the works that you can share with us?

I look for little ideas, small but interesting truths about childhood. The little idea behind Sleepyhead is that babies work very hard all day long -- crawling, reaching, bending their little necks back and up to see -- such that by the end of the day it is no wonder they are ready to collapse. The little idea that inspired Little Bitty Friends is that young children have a special relationship with other small creations. They will sit quietly and watch ants, they will happily hold a small beetle or a ladybug in their hands for much longer than you or I would, and they will bring their parents to a screeching halt on a walk because they have spotted a tiny rock or clover that they want to examine.

Once I have the idea -- and that's the hard part! -- the writing comes pretty easily to me. For 18 years, I was the editor of a journal on education policy and teaching practice. My contributors were mainly academics, so I was constantly writing and re-writing -- often on a tight schedule -- to make their prose more interesting and more accessible to a broad audience. Right now, I'm moving up an age bracket and trying to get inside the head of, say, a four-year-old, to understand how they explain the world to themselves. Why is the sky so high? The moon so far away? Why is there snow, why sand, why seas? How does a four-year-old think about all this? But I can't write until I get the motivating idea into one simple declarative sentence, and I'm not there yet.

What was the one book that turned you into a reader (or writer)?

I wish I had a classic answer -- an ah-ha moment -- and could recount an early reading experience that turned me into a lifelong reader/writer. It is certainly true that I love every aspect of the written word; I even like to diagram sentences! But how and why I developed this love is a mystery. I did not become a voracious reader till I was in my twenties, and although I did study literature for a while in college, I developed an interest in Economics and wound up doing my graduate work in that field. We had few books in our home when I was young. The only picture book I recall having was a book of verse. I do have vivid memories of listening in while my father read Treasure Island to my two older bothers. I would shiver as he imitated the sound of blind Pew's walking stick as he came down the road, and I poured over N. C. Wyeth's mesmerizing illustrations.

I did not go to kindergarten; it was not mandatory at the time, so I stayed home with my mother. When I was about six, we began to bike together to our public library. I come from a small town, and the library was not far away. Soon I was allowed to go on my own, and of course I loved that. But I can't say I was a big reader as a child. I had four brothers (no sisters) to keep up with, so I was mainly an outdoors girl. Except for the long hours we spent indoors playing bridge (my mother didn't play, and as the third child I became my father's best hope for a partner, so he taught me when I was just seven), for the most part my childhood consisted of equal parts on my roller skates, on my bike, playing kick-the-can, and standing in center field on a make-shift ball field. (My brothers, who had good reason to question my fielding abilities, would shout "Just keep going...farther, farther," and there I would faithfully stand, staring at the sun and with little action coming my way.)

So, I don't have a good answer for your question. My love of language must be in my genes, scrambled and served up from some long-ago inheritance. Why, for example, did I start writing from a young age? I have no idea. Nothing big, just small accounts of some visit or adventure or mishap. I would read them to my mother, and she would read them back to me. I knew little about books for young children until I had my own children. Then I went wild, of course. Almost all the books I read to them were a first-time read for me, also. Maybe that's why I read to them so much. Many years apart, we were discovering the same great books!

I first had the idea of trying my hand at writing for children only several years ago. I was caring for my husband, who had been sick for a long time and was terribly disabled with Parkinson's Disease. As such, I was pretty much confined to the house. A friend had her first grandchild, and as a present, I wrote a little book to give her. It didn't take me long, and it wasn't too bad, so I sat down and wrote three more. I sent them out to a half-dozen publishers and a half-dozen agents, certain that they would never make their way out of the slush pile (a term I didn't even know at the time). Within two weeks, and to my total shock -- it must have been a slow day is my only explanation -- I heard back from a major publisher and from the extraordinary person who would become my agent: Kelly Sonnack at the Andrea Brown Literary Agency. I really hesitate to relate this account because of course there are so so many writers vastly more talented than myself -- and that's such an understatement! -- for whom it took a long long time to make the connection to an agent or publisher. I have no explanation other than that I just got very lucky.

About the author:

A writer, editor, and late-afternoon napper, Elizabeth McPike lives in Washington, D.C. She is the former editor of American Educator, the professional journal of the American Federation of Teachers. On a perfect day, she is likely to be found in her garden or in the remainder section of her nearby bookstore or sitting in a quiet pew by a stained-glass window.